Choice and Agency in Energy Access

Forget electrons and energy services, true energy access is about choice

Beyond Electrons—The Power of Energy Services

Energy access is often discussed in terms of raw electricity—getting electrons to where they’re needed. But as the global push for universal energy access and SDG7 gained momentum, a pivotal shift occurred. We moved beyond mere electrons to focus on energy services—what people actually do with electricity: lighting, space cooling, refrigeration, entertainment, and more.

This transition, from supplying electricity to delivering tangible services, was a profound leap forward. But while this reframing was a major victory in making the problem of energy access more human-centered, an unintended side effect has emerged. We may have inadvertently overlooked a crucial aspect: human choice and agency. By fixating on what energy services people ought to have in the stepwise progression from extreme energy poverty to full energy access, we lose sight of the fact that how people choose to use electricity is driven by diverse individual preferences, economic constraints, and other contextual factors.

In this piece, I want to explore how we got here, celebrate the progress, and make the case for moving toward greater choice and flexibility as energy markets in un- and under-served areas mature.

Energy Access—From Electrons to Services

In the early days of energy access campaigns, the focus was primarily on supplying electricity — that is, getting “electrons” to rural areas or underserved populations. But the energy access equation is incomplete without access to appliances—the equipment that turns those electrons into usable services like lighting, refrigeration, or communication.

Today, we understand that the real gap isn’t just an electricity access gap—it’s an energy service gap. Billions of people globally lack the appliances necessary to convert electricity into these essential services, which is why the focus on energy services, rather than just electrons, was such an important evolution. This is particularly true in energy poor contexts where electrons are scarce, and appliances must provide service with constrained energy supply. This is why LEDs have been such a game changer for energy access—your lighting service can be powered by as little as 6 to 10 watts, compared to the 60 watts needed for an old-school incandescent light bulb.

This shift—from focusing on electricity to energy services—was a massive point of progress. It helped clarify the problem in concrete, people-centered terms and allowed for smarter, more targeted policy interventions. It shifts focus to what people can do with the electrons they have available, which is what matters. You see this in major energy access frameworks like the World Bank’s Multi-Tier Framework (MTF) and IEA’s energy service bundles, which explicitly link energy provision to specific end-uses like lighting and refrigeration when measuring and tracking access to energy in households.

While these frameworks have been instrumental in moving us forward, they are missing a critical piece: people’s agency. They tend to assume a neat progression from one appliance to the next — from basic lighting and mobile phone chargers, to radios and TVs, and eventually to refrigerators and air conditioners as households climb the energy ladder step by step. But human behavior doesn’t always follow such linear paths – and shouldn’t.

The Missing Piece—Human Choice and Agency

While the appliance-based hierarchies have been essential for prioritizing investments and helping people access basic services, they unintentionally sideline the complexity of human decision-making.

For example, in my own experience growing up in Nairobi, our household didn't follow any prescribed “energy ladder” model. We had no radio or fridge for most of my childhood, but had a 1970s desktop computer that literally occupied an entire desktop and an early-gen laptop that weighed a ton. Our appliance acquisition didn’t follow any linear model, and was based on the specifics of our life and context.

This is where we need to move beyond prescriptive frameworks. People make the choices they make, not based on policy guidelines but on what fits their lives. Human behavior, preferences, and constraints vary too much for a one-size-fits-all solution.

Bundling and the Early Stages of Market Development

In Sub-Saharan Africa’s off-grid solar market, the evolution of appliance bundling has been a key strategy for expanding access to energy services. Companies bundle appliances like solar home systems (SHS) with lights, radios, TVs and fans on pay-as-you-go models to deliver these services to households that wouldn’t otherwise afford them.

This model has been hugely successful in the early stages of market development – most off-grid appliances in sub-Saharan Africa are bundled with solar energy kits. Bundling allows companies to solve multiple problems at once: delivering power, stimulating demand, and providing financing options. In markets where consumers are still struggling with basic energy access, these models make a lot of sense.

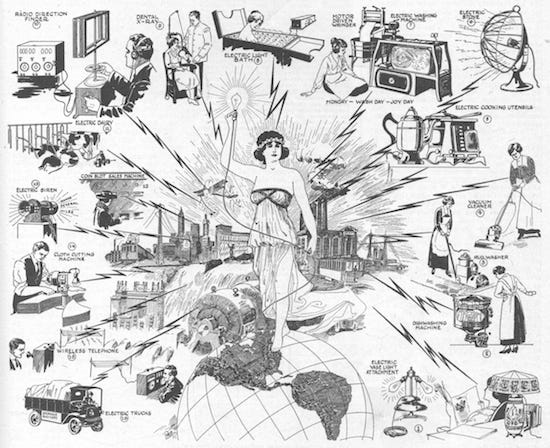

However, as these markets mature, bundling becomes less efficient. Over time, consumers will need more choice and flexibility, delivered through competitive appliance markets that can bring down costs. We’ve seen this dynamic before in the early days of US electrification, where utilities bundled appliance sales with electricity provision to increase adoption – in the 1920s and 30s, utilities were responsible for as much as 40% of appliance sales in the US. But as the market matured, regulations shifted, competition grew, and eventually, the system had to evolve to offer consumers more choices.

We’re witnessing something similar with the current state of EV charging. Today, EV charging standards vary by manufacturer and service providers—there are different connectors, charging protocols, proprietary networks, and payment systems. But as the industry matures, it’s moving toward more standardization and interoperability, which will ultimately lead to greater consumer flexibility and a more efficient market.

The lesson here is clear: bundling is a useful tool in the early stages of market development, but it’s not sustainable in the long run. As we look to the future, we should be moving toward systems that prioritize choice, interoperability, and consumer agency.

What Mature Energy Markets Look Like—Lessons from the US

In mature markets like the US, electricity has become ubiquitous and generic—a basic utility that underpins all aspects of modern life. The electricity itself is invisible, hidden behind walls and accessible with the flick of a switch or the push of a plug.

What’s notable in these markets is the total freedom of choice. Consumers can use their electricity for whatever purposes they see fit—whether those uses would be deemed essential (e.g., running an air conditioner during a heatwave) or frivolous (e.g., powering a video game console).

This is where energy access must evolve toward in the global south: a place where electricity isn’t a scarce resource allocated for specific uses, but a generic utility that people can use freely to meet their own unique needs.

Centering Agency in the Future of Energy Access

As we continue expanding energy access, it’s crucial to celebrate the progress made in moving from electrons to energy services. Frameworks like the World Bank’s MTF have been instrumental in driving this conceptual evolution. Appliance bundling, too, has been necessary in developing energy markets that can deliver these services, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa’s off-grid sector.

But as we look ahead, we must prioritize people’s agency. The ultimate goal is not just to provide electricity or even services, but to ensure that people have the freedom to make their own energy choices—just as consumers in mature markets do.

True energy access is not just about delivering the right appliances in the right order. It’s about creating the conditions where people can choose for themselves how to use the electricity available to them. As we build for the future, we must keep human agency at the heart of our policies, ensuring that choice, not just electricity, powers progress