A Skeptic’s Guide to Tech Hype

Hype is both a feature and bug of tech innovation

We seem to be living in the age of peak hype. All around, new buzzy technologies — from AI to crypto and blockchain — are threatening to disrupt everything.

This means that we are also living in the age of peak anti-hype, the counter-reaction within the opinion-sphere to these sweeping narratives about the future of tech in society. Quantum computing? Hype curve is growing exponentially but the commercialization curve is going nowhere. Crypto? Hollow profiteering and shenanigans. AI? Get ready to be disappointed. Green Hydrogen? A risky gamble. Self-driving cars? Nowhere to be found.

I’m no stranger to this form of tech-hype skepticism — two of my most recent articles were on the pitfalls of radical techno-optimism and misguided AI buzz in Africa, and I am a known critic of tech silver bullets in the international development space. So, why this reappraisal of tech hype and its potential benefits?

Balanced and thoughtful anti-hype commentary is an important corrective to overblown claims and flavor-of-the-month fanaticism that typically accompanies exciting new technological breakthroughs. Unchecked, overfocus on shiny objects can divert precious resources and attention from other important solutions. This anti-hype posture thus has value, but is also subject to its own oversimplifications about the way tech can develop over the long run, and underestimates the ways in which hype cycles are not just bugs but also features of tech innovation.

What I Learned from the Nanotech Hype Bubble

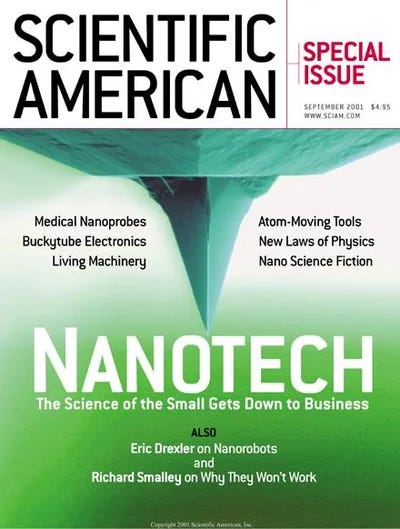

Recently, I was reflecting on my time as a doctoral student in the late noughties to early twenty-tens. My PhD research focused on nanoscale device and polymer physics, plus some neat theoretical and computational work on nanowire networks. All these years later, and many anti-hype thought pieces later, I somehow managed to forget that I once literally lived inside a massive tech hype bubble — doing a PhD in nanotechnology in the middle of peak nanotech mania.

The first decade and a half of the 21st century were indeed heady times for the nanotech world. Sweeping predictions on how it would revolutionize everything from manufacturing, health and electronics were commonplace, fears about how it would destroy society were stoked (remember the killer nanorobots?), and investors jumped on the bandwagon to get a piece of the pie. Sound familiar?

The counter-reaction to nanotech hype followed closely behind, and by 2016 nanotech fatigue had officially set in, and as these things go, Elon Musk had the last word on the subject when he dismissed nanotech as BS shortly after.

It turns out, as I have learned during my recent reflections, that looking at nanotech nearly a decade past its hype cycle can teach us a few interesting things about the nature of tech hype itself.

1. Don’t measure impact by the hype yardstick

In dismissing over-hyped technologies, we may be inadvertently using a hype yardstick to measure tech progress. It is true that hype does not guarantee long-term success and impact. However, a technology can fail to meet hyped expectations and still have a significant impact in society. Nanotechnology is a great case in point.

Nanotech is an old (its modern scientific roots can be traced back to the 19th century) and broad branch of scientific research and technology development loosely bound by a common focus on phenomena at the nanoscale (between 1 to 100 nanometers, with one nanometer equal to a billionth of a meter). As a result, a diverse range of research and technologies fall under the umbrella of nanotechnology, all with the idea of exploring and exploiting interesting physical properties that manifest at the ultra small-scale.

This back-end and multi-functional nature of nanotech means that it shows up in society in forms that are not immediately recognizable. Nanotech is embedded in our TVs (e.g. Samsung's QLED and LG’s QNED models) and other screens; in our faster and more powerful computer processors (processors with feature lengths below 100 nm have been around for over two decades, and major players like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and Intel have processors with feature lengths smaller than 10 nm in the market); in the growing list of cancer treatments based on nanotechnology, and even in our cosmetics such as sunscreen and anti-aging creams. Nanotechnology is also invaluable to scientific research itself, driving new scientific discoveries by enabling researchers to manipulate and study matter at the atomic and molecular levels. Nanotech is also posing real risks to society (such as potential human and ecological toxicity risks), even if the killer nanobots are yet to arrive.

Measured against hyped expectations, some anti-hypers have concluded that nanotech belongs on the list of over-hyped technological failures. But behind the scenes, with minimal fanfare, nanotech is clearly having deep and wide-ranging impacts across society. By assessing the long-term success of hyped technologies against the inflated benchmarks set by the hypesters, skeptics risk missing how these technologies might be transforming society in other significant ways.

2. The golden rule of the future: Humility

There is more to come for nanotech. New paradigms, new discoveries, new applications at different stages of the innovation pipeline from basic research to commercialization. And also: new disappointments. This is true for any given field of research and innovation, buzzy tech fads included.

Tech trajectories are highly uncertain, which is another way of saying that we don’t know the future. There may well be a future in which AI overlords take over, perhaps commanding an army of killer nanobots. Or a (less dystopian) future in which self-driving cars are ubiquitous and everyone has access to tailored treatments that deploy nanobots to deliver medication to specific targets within our cells. Over-hyped tech fads that we dismiss today could surprise us in the future, so both the tech fanatics and anti-hype reactionaries should keep an open mind even as they prognosticate on what will come next in the world of tech.

3. Hype can drive crucial foundational investments

Finally, riding the hype wave can give researchers doing important work on the margins a shot at getting much needed attention, funding, and partnerships required to unlock the next level of achievement in their field, while also building foundations that will help sustain future work when the excitement inevitably moves elsewhere.

The rise of nanotechnology in the noughties demonstrates this well. By repackaging and giving a fancy brand name to diverse streams of existing research unified by a common interest in manipulating matter at the atomic and molecular scale, it created a compelling narrative that effectively drew public attention to this work. This fed the hype machine, but was also hugely successful in channeling billions of dollars in basic research funding into the space. This funding went into building new research facilities, buying state-of-the-art equipment, training numerous doctoral and postdoctoral researchers (myself included), and supporting the creation of new scientific knowledge. These are long-term investments into scientific infrastructure, workforce development, and the knowledge commons, rather than flash-in-the-pan ephemera implied by the hype tag.

Hype is both a bug and a feature of tech innovation

Tech hype cycles come and go, and the public interest in specific technologies waxes and wanes. Like Heidi Klum’s signature phrase about the world of fashion: “One day you’re in, and the next day you’re out.” And then, many days later, you’re in again —just like hydrogen, which is currently trending in clean energy and tech circles decades after its original hey-day during the 1970s oil crisis.

These cycles exist precisely because we often don’t know what will work, when it will work nor how it will work. We can’t get rid of the buzz, but we need to see it in its broader context and harness it productively.

An effective antidote to the kind of unproductive buzz that we anti-hype commentators are justifiably worried about is diversity. First, we need to keep investing in diverse upstream research that maintains a rich pool of ideas and knowledge from which future breakthroughs will be drawn — whether or not they hit a hype cycle down the road. Second, we need a diversity of big ideas that capture the public’s imagination on any given issue, rather than the reductionist view that presents a particular silver bullet as the one solution worth caring about. Capturing the public’s imagination need not be a zero-sum game, it could also grow the pie that researchers and tech pioneers have to share.

Meanwhile, the field of nanotech is way past its hype peak but marches on — and just bagged the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.